Some intuitive writers sit down at their desks with no more than the wisp of an idea in their heads, and let the story unfold as they write. That’s never been me. I don’t write a word of my books until I have worked up a clear outline of the story from beginning to end, scene by scene, chapter by chapter. As I do so, I scribble down a couple of sentences describing what will happen in each of those scenes on a stack of 3”x5” notecards, outlining how the story builds and turns, what each beat contributes to the plot.

Day after day, week after week, that pile of notecards grows on the side of my desk. I may sketch a scene a dozen different ways before deciding which one to choose. Ninety percent of my ideas, I later discard.

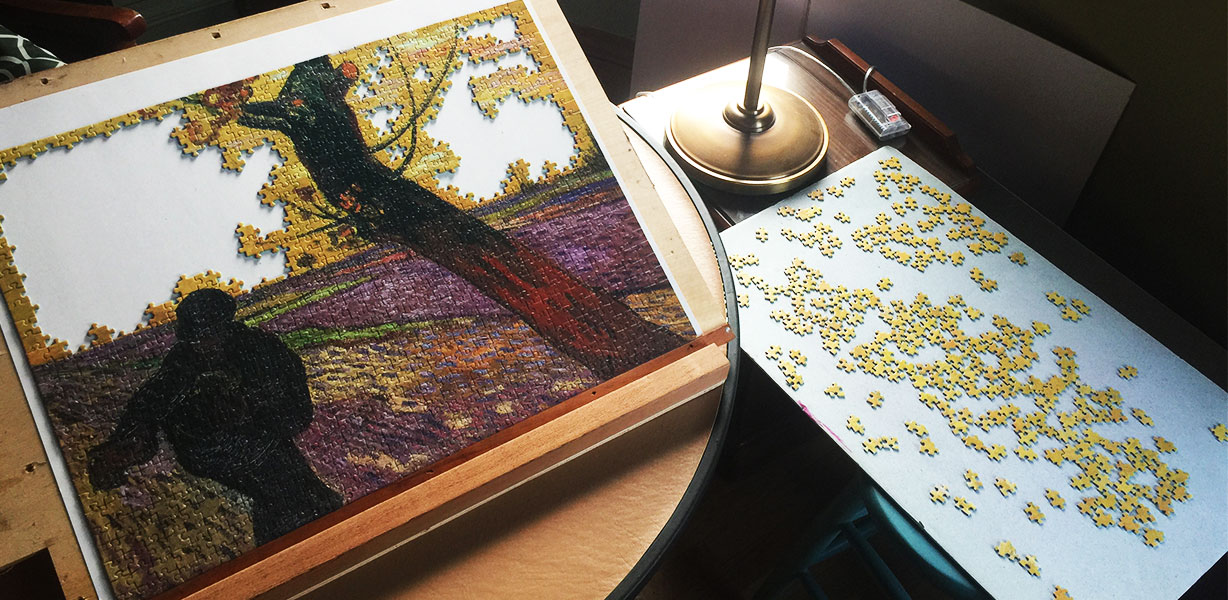

And then, when I finally reach the end of the story, it’s time to put it all together, in order, everything in the right place. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle, working out which scene should go where, how to develop character and plot, pacing and suspense. Only I don’t have a picture on the box to guide me. Often I get stuck. Frequently, when I actually start writing, even with all my careful, painstaking planning, the characters show me sides of themselves I didn’t anticipate. The story takes off in surprising directions, and suddenly all my neat cards are metaphorically — and occasionally literally — tossed in the air, scattering ideas everywhere. When that happens, I quit trying to write and go into my sitting room, sitting down at the jigsaw puzzle table set up in the corner. I always have a puzzle on the go; as soon as I finish one, I start another. Most are one thousand to two thousand pieces, and I never do any of them more than once.

There’s something soothing, almost hypnotic, about turning the pieces of a puzzle over in my fingers, blue sky, gold leaf, working out by eye where each should go. Sometimes, I’ll pore over the table for half an hour, just looking, and then, as if by instinct, I’ll know which piece to select, and where it fits.

And in the process, somehow the pieces of my plot will come together, too. It’s like my brain is sifting the scenes in my head as my eyes search the pieces on the table, choosing and discarding, until I suddenly know exactly what happens in the next scene, where the story should go. My son, Henry, who is a talented carpenter, made me a jigsaw table to save my back, because I can spend several hours at a time hunched over the puzzle, waiting for the story to work itself out.

I can only compare it to a kind of meditation. My mind is so engaged with the jigsaw, it stops fretting about the story, and the elements come together, exactly as they are meant to.

The only other time I experience the same kind of sensation is when I’m rock-climbing in the south of France, my body and brain utterly consumed by the need to select the next hand-hold, where to put my foot. There’s no spare mental hard-drive to worry about anything but the next choice. Working on a jigsaw is a little more practical, however — and a lot more pleasant in the winter!

In the end, it’s about letting go, and allowing your subconscious mind to come to the fore. Working on a puzzle is like white noise, getting rid of the monkey-mind chatter that otherwise fills my head, allowing me to hear that inner voice that’s telling me the story.

Those moments when the words just flow, when the story seems to tell itself, are my reward for those long, difficult, laborious hours with my notecards. And ultimately, the reader finally gets to enjoy the full picture, made up of a thousand individual pieces that somehow come together to form a cohesive whole.